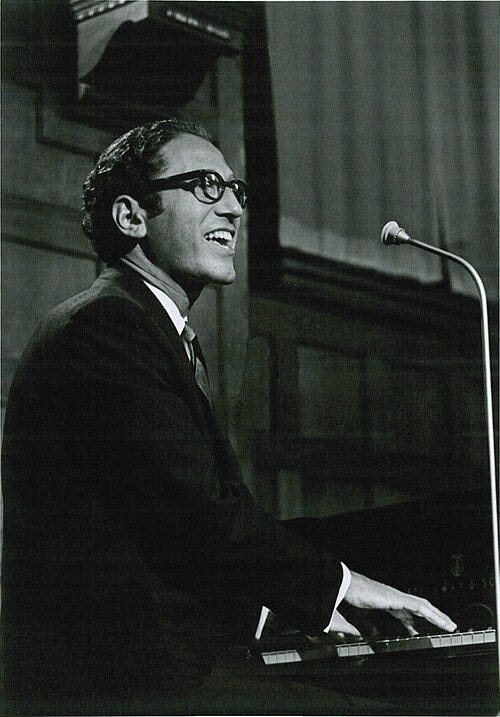

Last week Tom Lehrer joined countless pigeons in eternity. His death occasioned many to revisit his repertoire. In it one hears much to admire. Had Lehrer written only “Wernher von Braun” or “The Vatican Rag” he still would have earned the many obituaries which flooded our feeds after the announcement of his death, unanimous in their praise.

But while reading those obituaries last week I also found some cause to wonder. What gave him the wisdom in 1972 to forego the temptations of further fame and instead return to mathematics? How did he manage such popularity while weaving into his songs such wonky topics as the multilateral force? And how did a child of the academe with a taste for contravention end up in the U.S. Army?

It’s that last question that this brief post considers. Lehrer was a math prodigy who spent his school days in ivied cloisters like Horace Mann and Loomis. At age fifteen he started at Harvard, penning satirical songs for buddies when not flying through his coursework. By the time he was twenty he had finished his master’s. Indications were he would spend his life studying number theory and cracking jokes to music.

Yet for a two year interlude Tom Lehrer, who so deftly made an art of irreverence, wore the uniform of his country. How did that happen? The shortest answer is probably the Universal Military Training and Service Act of 1951. The Berlin crisis and Korea taught Congress that the standing army somehow survived both the Second World War and the atom bomb. Policymakers now spoke of a need for “enduring strength.”1

To meet that need, the draft law of 1951 shrank the number of ways a young man could defer military service.2 The band of eligibility expanded both up and down the continuum of education. Neither poor scores on draft exams nor graduate study could as easily exempt a potential draftee. In the 1950s, schooled and unschooled America began meeting at basic training with greater frequency than ever before.

The 1951 law did preserve some havens from the draft boards, such as work in essential industries. Where was the essential work? At Los Alamos with the Atomic Energy Commission, or, say, in Cambridge with Atomic Instruments Company. And those are the sorts of places one could find Tom Lehrer during the Korean War.3 But by ‘53 Lehrer concluded, in his own words, that “nobody was going to shoot me and I wouldn't be called upon to shoot anybody else.” So he reported to the draft board. By ‘55 he was in uniform.4

The Army Tom Lehrer joined is described well in Elvis’s Army: Cold War GIs and the Atomic Battlefield by historian Brian MacAllister Linn. It was by then America’s “most racially and economically egalitarian institution— the only place where members of every ethnic group, college graduates and illiterates, rich and poor, urban and rural, had to live, work, train, and if necessary fight together.”5 And that Army’s senior brass was utterly preoccupied with the role of any army in the shadow of a mushroom cloud.

The mushroom cloud certainly would make its share of appearances in Lehrer’s repertoire. But so would the egalitarian Army into which Lehrer enlisted. It did so most memorably in his “It Makes A Fellow Proud to Be A Soldier.” One might read into it some reference to the much-reduced cognitive standards for draft eligibility codified by the 1951 law:

Now Fred's an intellectual, brings a book to every meal.

He likes the deep philosophers, like Norman Vincent Peale.

He thinks the army's "just the thing"

Because he finds it "broadening."

It makes a fellow proud to be a soldier.

Now Ed flunked out of second grade and never finished school.

He doesn't know a shelter-half from an entrenching tool.

But he's going to be a big success.

He heads his class at O.C.S.

It makes a fellow proud to be a soldier.

…Our captain has a handicap to cope with, sad to tell.

He's from Georgia, and he doesn't speak the language very well.

He used to be, so rumor has,

The dean of men at Alcatraz,

It makes a fellow proud to be

What as a kid I vowed to be,

What luck to be allowed to be a soldier.

At ease!

We should probably take Lehrer at these and other (ironic) words, which suggest strongly that he didn’t much enjoy his time in the service. He would not be the first brilliant mind to find the drudgery of military life intolerable. But his words, or at least those I can find, also leave little hint as to whether he was aware of just how remarkable the Army he joined was for its democracy. As Linn puts it, it is “illustrative of how large the military loomed in the lives of young men in fifties America that Lehrer’s Harvard audience would understand his references to “captain’s bars,” “R.A.,” and “OCS.””6

It wasn’t for long. Lehrer got out of the Army after his two years on active duty, with loads more material than perhaps his fertile mind needed, and went on to sell many records before settling into a career of mathematics. Still, the episode is telling. To know that the U.S. Army could accommodate a mind such as Lehrer’s, on such egalitarian grounds, moves one to salute the both of them, and say, without a trace of irony, that it makes a fellow proud to be a soldier.

“Summary of Report on Universal Military Training; REPORT TO CONGRESS ON UNIVERSAL MILITARY TRAINING” New York Times, October 29, 1951. https://www.nytimes.com/1951/10/29/archives/summary-of-report-on-universal-military-training-report-to-congress.html

Harold Hinton, "DRAFT-U.M.T. BILL SIGNED BY TRUMAN: HE NOMINATES 5 TO SUPERVISE MILITARY TRAINING PROGRAM --MARSHALL HAILS LAW DRAFT-U.M.T. BILL SIGNED BY TRUMAN MARSHALL ISSUES STATEMENT EFFECT OF DRAFT LAW EDUCATIONAL DEFERMENTS." New York Times, Jun 20, 1951.

Nicole Arthur, “Tom Lehrer, master satirist of the Cold War era, dies at 97”, Washington Post, July 27, 2025. https://www.washingtonpost.com/obituaries/2025/07/27/tom-lehrer-satire-music-dies/

Bernstein, Jeremy. “Out of My Mind: Tom Lehrer: Having Fun.” The American Scholar 53, no. 3 (1984): 295–302. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41211046.

Brian McAllister Linn, Elvis's Army : Cold War GIs and the Atomic Battlefield (Harvard University Press, 2016), 5

Ibid., 197