Topical, Polemical, Short

Shallow reading and the American Revolution

Of late many have written about reading. It has been said that ours is a post-literate age. It has been said that ours is not. It has been said that literature can save your soul. It has been said that literature cannot. It has been said that without books we will become barbarians. It has been said that with books we already are. Though they may disagree on stakes or effects, these pieces share underlying concerns, about our society’s health and our own health and the effect of what we do or don’t read on both.

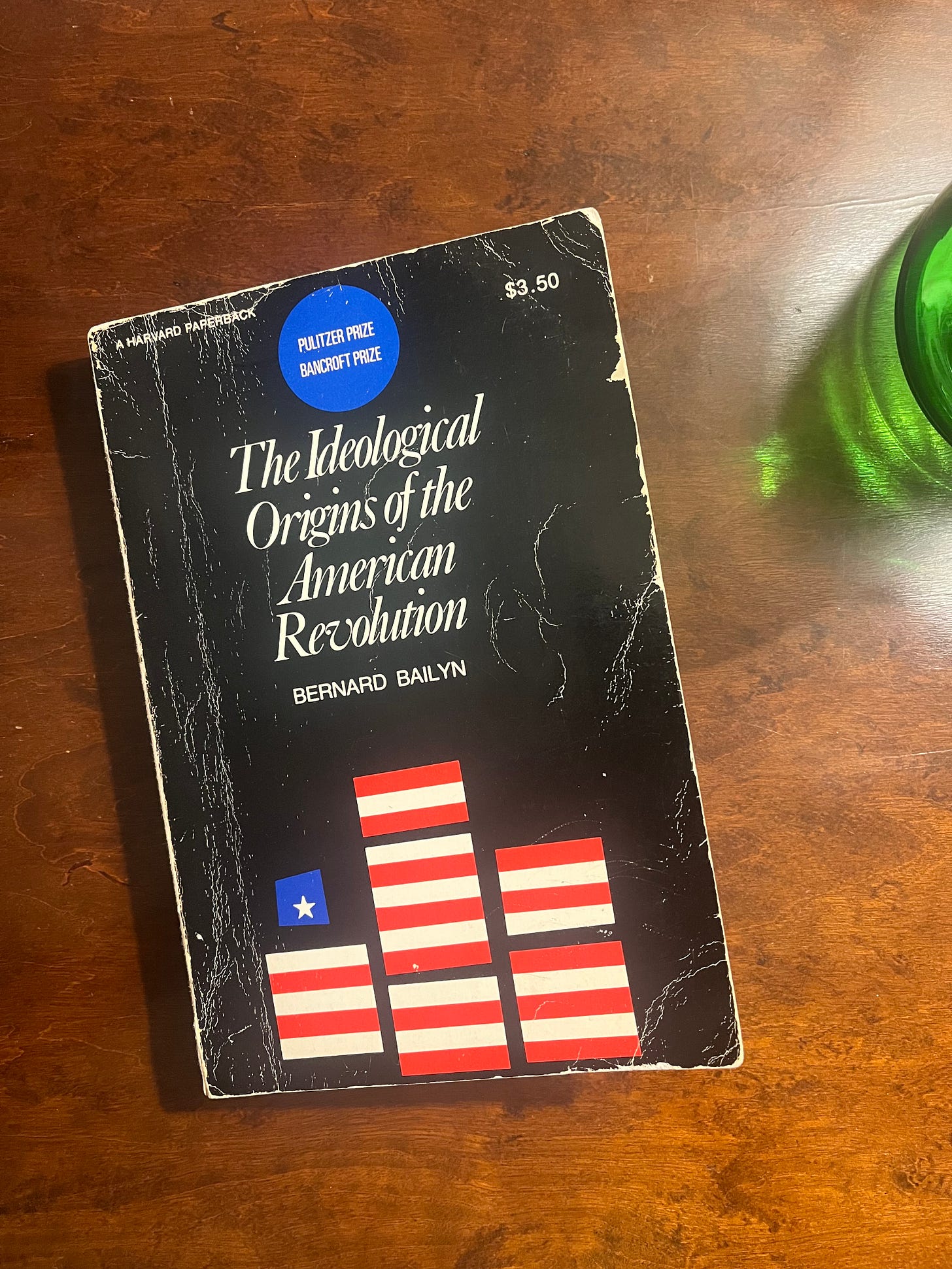

To heed these posts about the death of literary culture, I stopped reading them. Instead I returned to a book I had set down earlier this fall. It is The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution by Bernard Bailyn. After all, yesterday was the anniversary the British surrender at Yorktown that brought that titular revolution to a happy end (how did you celebrate?) But I found that while reading Bailyn, rather than escape that many-headed literary discourse, I only returned to it. That is because The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution is about nothing if not the effects of one’s reading.

Bailyn’s case is this: the American Revolution was born of a shared political consciousness. That consciousness arose from a vast circulation of of innumerable pamphlets in the colonies.1 These pamphlets were written by amateurs with middling imaginations. What the pamphleteers lacked in art and learning they made up for with their directness. In their pamphlets they described a vast conspiracy devised by a venal English ministry to strangle the great tradition of English liberty. By the 1770s the pamphleteers concluded that the last best hope for that great tradition was revolution in the colonies.2 To make this case, Bailyn offers a study of the colonist’ minds so attentive and well-rendered it won him in 1968 both the Bancroft and Pulitzer Prize.

Note that Bailyn does not consider the pamphlet (he likes Orwell’s definition, which includes three criteria - topical, polemical, short) a mere conduit for ideas originally found in great books. The works of classical antiquity, Enlightenment rationalism, New England Puritanism and English common law all played a role in moving the colonists to revolt, but theirs was a secondary role.3 The seemingly endless classical allusions made by the American revolutionaries in oration and writing obscure, per Bailyn, “the high selectivity of their real interest and the limitation of the range of their effective knowledge” Most of the time, high-flying references to the ancients instead amounted to what Samuel Johnson called “window dressing.”4

The same superficiality often marked colonial reading of the Enlightenment rationalists. In their political spats the colonists cite John Locke at times quite well but “at other times he is referred to in the most offhand way, as if he could be relied on to support anything the writers happened to be arguing.” Loyalist and revolutionary alike find a friend in Pufendorf and Montesquieu. Voltaire too proved for them quite flexible. Bailyn detects in the universal application of such authors, a shallow, or at least uneven, understanding. So too were appeals to English common law often “vague in intent” and invocations of Puritan cosmology rather blurry.5

This argument is less obvious than it might sound. Bailyn’s point is that most of the revolutionaries were not inspired by what we today might call “deep reads.” Instead, the intellectual prime mover of the American revolution was a corpus of amateurish, at times reductive pamphlets, given to disquiet and written for mass consumption. The Revolutionary-era pamphlets may now seem to have merely popularized or synthesized more important original thinkers, but Bailyn argues the extraordinary element at work was the rhetoric of the pamphlets themselves.6

These pamphlets were in some ways familiar to us. They were accessible. They were grandiose. They came laden with cartoons. They were sarcastic. They were allegorical. They could spin out into long acid exchanges and feuds between competing authors. And they peddled, for lack of a better term, conspiracy theories. Or so argues Bailyn:

The danger to America, it was believed, was in fact only the small, immediately visible part of the greater whole whose ultimate manifestation would be the destruction of the English constitution, with all the rights and privileges embedded in it. This belief transformed the meaning of the colonists’ struggle, and it added an inner accelerator to the movement of opposition. For, once assumed, it could not easily be dispelled: denial only confirmed it, since what the conspirators profess is not what they believe; the ostensible is not the real; and the real is deliberately malign.7

None of this is to say that John Adams suffered the same strand of brainrot now apparently rampant thanks to the exquisitely designed user interfaces of most media platforms. It’s just to say that today’s readers are not alone in confronting a froth of fractious, charged, imprecise and conspiratorial stuff. Ironically, Bailyn says the colonists read the authors of classical antiquity not to commune with antiquity on its own terms but because those authors, if narrowly understood, appeared to share the colonists’ concerns:

They had hated and feared the trends of their own time, and in their writing had contrasted the present with a better past, which they endowed with qualities absent from their own, corrupt era. The earlier age had been full of virtue: simplicity, patriotism, integrity, a love of justice and of liberty; the present was venal, cynical and oppressive.

It’s hard not to detect today a similar wistfulness about the past. One can take this either as dispiriting or reassuring - either things have always been that bad or things are better than they seem. The warm intelligence of Bailyn’s work is at least one reason to one choose the latter.

Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1977), 17. Bailyn makes specific claims about the shallow imagination of these works, with exceptions made for Thomas Jefferson and Adams.

Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1977), 17-21.

Bailyn, The Ideological Origins, 34

Bailyn, The Ideological Origins, 25

Bailyn, The Ideological Origins, 29, 31-33

Bailyn, The Ideological Origins, 45-46

Bailyn, The Ideological Origins, 95

As a dutiful American, my first instinct is to rebel against this argument—after all, these men were hardly uneducated when you actually read their writings. The basic literacy level/reading comprehension in the colonies was low, and must be accounted for, so they had to make the argument accessible for the masses.

However, the closing point cuts well. I just finished This Kind of War. There’s the feeling amongst people—usually in their 50s and 60s—who speak of the grit of the young, and how they’re not as textured as them or their fathers. But when you really look at things, they are much the same in that realm. Yet certainly, social media is a new beast altogether, and the true effects not yet developed enough to know although emerging.

Very nicely done. When doing intellectual/political history, I think one must distinguish between thought (self-conscious, problematic, contested) and the construction of a world, Weltanshauung. The former may contribute to the latter (Rousseau and the French Revolution springs to mind), but it is the latter that matters for politics, for going to war, for the sense (and nonsense) of a particular time. So yeah, pamphlets matter.